These are all the books I’ve finished throughout 2025, in somewhat chronological order.

These are not reviews. There is no five-star scale. These are just things I thought were interesting from each book, quotes that I find significant, how I came into contact with these books, some of my thoughts, and a potential recommendation for specific people. Everything is clearly biased and subjective. It is intended to be subjective.

There are a lot of quotes I’m still trying to fully understand, and I haven’t explained anything as well as I’d like to. But it is December and I should write something to remember what I learned, so here we are. I hope you find this helpful or interesting in some way. If you have book recommendations for me, please text me on whatever platform you found this blog!

*Best viewed on laptop.*

The Sense of Reality: Studies in Ideas and Their History

Isaiah Berlin

Nonfiction, Essays

Would recommend if you are: interested in Marxism, enjoys philosophizing about human nature, society, art, likes essays analyzing abstract concepts.

“Art gains nothing from being told that it is intelligent, truthful, profound, but unpoetical.”

Bought this book along with a couple of other political science books that were on sale. It’s a long read, but I really enjoyed the diversity of topics included in these essays, especially the way it muses over broad concepts like art and Marxism through examining their base characteristics and the way our perceptions of them has changed over time. The examples are Eurocentric, but the arguments are conscious of the Western bias. Worth serious study and would love to read again.

- Historians alternate between sticking only to proven facts about the past and representing an extremely limited history of objects, and narrating imagined stories of past human lives—aesthetic, religious, moral—that may not stand up to a facts-based scrutiny.

- Good politics shouldn’t look for a fixed utopian society where everyone agrees, because each individual has unique wants and needs inevitably contradictory with each other. Instead, the goal should be to create institutions and norms that minimizes the suffering caused by the disagreements that will always exist.

- There are certain human values that precedes Marx’s explanation of the world as the expression of a superstructure determined by an economic base, but Marxism’s appeal can be even stronger than religion: by characterizing historical progression as inevitable, Marxism enables the impoverished to act and organize, rather than merely understanding their exploitation or protesting through institutional means—while guaranteeing their eventual success.

- In contrast to the traditional Western belief that rational argument and persuasion is possible across backgrounds and identities, Marxism doesn’t believe that communication is possible since the facts of the world are different based on the individual’s economic position. Hence individuals can abandon the capitalist class, but the capitalist masses are irredeemable.

- Good art comes both from the aesthetic and the individual’s talent in conceiving it, and the author’s passion and feelings that solidifies into an idea the author commits to. Good art is embedded with the author’s own history and interpretation of ideas from their surrounding world. Art and creative work has to connect to lived experience, to come from the reality of being an engaged citizen in one’s society.

- Leaders that preach internationalism and free trade and disarmament, who views the world as one society of mankind, forgets that there are peoples for whom recognition and justice and basic means of survival are still absent. People who are dispossessed by colonialism must first develop on their land by themselves with their own cultures and languages, with their own collective memory, and not in cultural or economic debt to an outside state; the prerequisite of unity is equality between nations. This is the core of nationalism and the strongest justification for self-determination.

- You cannot prioritize happiness as the final good, because happiness is meaningless if there is no freedom to choose otherwise, the freedom to have remorse for choices you could’ve made differently, the potential for sin—to deprive someone of their free will even for a good as important as happiness is undesirable, because a human good cannot have priority over the quality of being human in itself, which is indistinguishable from the perception that one has choice.

- Humans have a base need to question and argument on what is truth. It is an end in itself necessary to personhood, and any attempt to surpress this need—for stability, for nation-building, for any historical reason—is an unsustainable surpression of a base human need. This is why philosophy is dangerous, because the discipline in essence, despite its abstraction, is endless questioning of the status quo.

THUD!

Terry Pratchett

Fiction, High Fantasy

Would recommend if you are: in a reading slump, enjoy British humour, enjoy fantasy, or believes that reading is the most boring activity in the universe.

“It was written in some holy book, apparently, so that made it okay, and probably compulsory.”

I first read a Discworld book from a tutor groupmate’s recommendation (thank you Victor!) in 2023, my first year of high school. This is the series that made me truly fall in love with fiction again, and it is the best introduction to fantasy that I can imagine. The wit, the narration, the plot, the characters, and the magical city of Ankh-Morpork drew me in immediately. It reminded me that reading can be extremely fun while making me think. I was on a marathon to get through all of them, but then I realized that the more I read the less I had to read in the future, as there are only forty-two books. I am saving the rest for a future time where I need the magic of Discworld again.

If you’re interested in starting, the usual recommendation is to start with Mort (if you’re interested in Death, mortality, humanity, etc.), Small Gods (if you’re interested in religion and belief), or Guards, Guards! (if you’re interested in law and justice). Here is a flowsheet that explains the logic of the reading order.

(I really should write down my memory of Reaper Man, The Hogfather, and Night Watch…What incredible, incredible stories.)

- Fantasy as allegory is such a powerful tool for social commentary. You’re reading this silly feud between dwarves and trolls and the police’s role in all of it, and suddenly you recognize more and more of the hatred and violence and misinformation and all the characterizations of these creatures and you see that it’s not really about dwarves and trolls. Pratchett is spectacular with developing a silly fantasy setting into what realistically would occur if it existed: in the city of Ankh-Morpork, what would happen if races were to live next to each other? How would the existing stigmas regarding each race — dwarf, troll, vampire — manifest in the workplace, in relationships, in the public treatment of individuals?

- Pratchett’s characterization of Sam Vimes throughout the series is my favourite characterization of police in any fiction. He’s the Commander, and he tries his best to do his job well, to do the right thing, and he’s got the skills and the personality for the line of work — but he’s also a recovering alchoholic, he has racist and sexist beliefs that he gradually becomes conscious of throughout the series, he has a short temper and isn’t very polite, his work-life balance is not balanced at all … but what Pratchett does so magically is how he guides the reader to empathize deeply with Vimes and how difficult his work is, how hard it is to remain just and search for the truth in a system that rewards the opposite. We see him as an imperfect but good officer, imperfect but good leader, and, eventually, an imperfect but good husband and father. Vimes is such a rich and likeable character that he charms the entire Watch series through. The Watch series and the Death series are my personal favourites. I also read Equal Rites this year, but it didn’t leave a lasting impression on me, so I’m highlighting THUD! instead.

- Personally a big fan of cities that are alive and speaks to the character/you (e.g. Fallen London, Disco Elysium, etc.) Ankh-Morpork is brilliant for this reason. More on this later.

- There are so many footnotes. I really enjoy the feeling of the author, while narrating the story, speaking directly or explaining things to the reader. The footnotes contain a lot of jokes as well.

- There are so many jokes. I have definitely missed a lot of references and jokes. This is why I need to reread all of them immediately to find what I’ve missed. God, what would I give to read Discworld again for the first time…

A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again

David Foster Wallace

Nonfiction, Memoir

Would recommend if you are: really into sports (tennis in particular), dislikes cruise ships, likes listening to someone explain their observations about people, or finds the world and our place it it to be, in its essence, strange and a bit sad.

“And this authoritarian — near-parental — type of advertising makes a very special sort of promise, a diabolically seductive promise that actually kind of honest, because it’s a promise that the Luxury Cruise itself is all about honoring. The promise is not that you can experience great pleasure, but that you will. That they’ll make certain of it. That they’ll micromanage every iota of every pleasure-option so that not even the dreadful corrosive action of your adult consciousness and agency and dread can fuck up your fun. Your troublesome capacities for choice, error, regret, dissatisfaction, and despair will be removed from the equation. The ads promise that you will be able — finally, for once — truly to relax and have a good time, because you will have no choice but to have a good time.”

The first time I heard DFW’s name was while watching his graduation speech, This is Water. The speech continues to move and influence me to this day. I had read some quotes from his other works online, but this was the first full work I read from him. I look forward to one day attempting Infinite Jest.

- DFW writes observations/commentary about people with extreme attention to detail and lays bare his own assumptions about what those details infer about the person’s background and character. DFW describes people with such interesting metaphors and vocabulary: for example, he described the bodies of the middle-aged sunbathing passengers on the cruise ship as being “in various stages of disintegration”. It’s less deduction than building each character through his observations, which allows us to experience their personalities through his eyes, while also being suddenly aware of the limitations of their personalities. This book is mainly about sports, his observations of people on a cruise ship, and some musings about art. It is the way he writes and characterises each subject, and the way he formulates his own musings, that makes these observations interesting to someone completely ignorant of the subject matter.

- The way DFW narrates reminds me of how Yiyun Li described how she sees the world: a combination of intense attention and, in a way, apathy. In my reading of DFW, however, I think the apathy is a pretense for his deep empathy with the weak and imperfect people around him, who became this way due to a cold, unfeeling world. The narration seems descriptive, detached, though detailed, but I think it is deeply, thoughtfully sad.

- Wallace talks a lot about sports, especially his younger self’s partial undertaking of the journey and his second-hand knowledge of life as a professional athlete: to be the very best at a skill and believing that giving up everything else would be worth it. DFW observes that, while the public seems to respect the sacrifices professional athletes make, admiring their diet and training and loneliness, we then scorn the actuality of those sacrifices, the illiteracy and tendency to do drugs, lack of social awareness, etc. There is no “rounded human life” consisting of “values beyond the sport”. They can only be what they are when they are fully committed to that pursuit, “a consent to live in a world that, like a child’s world, is very serious and very small”.

- I think DFW would have a cool conversation with John Green about despair. DFW describes the word despair as being “overused and banalified”; in reality, despair represents a combination of “a weird yearning for death” together with “a crushing sense of my own smallness and futility that presents as a fear of death”. It sounds contradictory, but it makes sense in a way: despair makes you want to die because you don’t want to see yourself as who you are anymore. After all, what we all are is “small and weak and selfish” and definitely going to die. I don’t know if I agree with this, but the observation is interesting to think about — what, then, should we do when we experience despair? I think “small and weak and selfish” is part of what we are, but not the whole of what we are, in the contexts of the multitudes we contain.

- While describing the cruise, DFW notes something interesting about advertisement: when you perceive art or something made with artistic intent, you lower your guard because you believe that its only intention is to express, that the author is pure and honest about their work. But advertisement made in the form of an essay, advertisement hidden by the author within a performance, even if it’s great artistic advertisement — not only is it dishonest, but also, since its selfish nature disguises itself as “goodwill”, it makes people no longer able to discern between genuine art and advertising, making the audience“feel confused and lonely and impotent and angry and scared. It causes despair”.

The Overstory

Richard Powers

Fiction, Novel

Would recommend if you are: a nature-lover, enjoys beautiful prose, in a reading slump.

“For there is hope of a tree, if it goes down, that it will sprout again, and that its tender branches will not cease. Though the root grows old in the earth, and the stock dies in the ground, at the scent of water it will bud, and bring forth boughs.”

Saw mentions of this book online, and found the physical copy by chance in the school library. The book was so moving for me that my solo film project for my film portfolio was heavily inspired by this novel, shown here below.

- This is one of the most beautiful stories I’ve read in the past few years about nature, the timeless wonder of it on its own and individual humans’ complicated relationships of love and exploitation with it. I love how the author describes each tree with the same importance as he would allocate to a human subject, and that forests and trees in this novel are not a plot device but central characters in this story. As someone whose life consists of very little nature, reading The Overstory gave me a sense of reverence and awe for trees that I rarely experience in real life.

- I’m not usually one for splitting multiple plotlines across chapters so that more than one story is told simultaneously, but I think Powers made it work here, especially in how the individual stories gradually become linked with each other towards the end. The characters and their stories are all bound to trees and nature in different ways, and their characterization reflects the centrality of trees to their narratives. The author makes the trees metaphors for people and the people metaphors for trees.

- The prose is soothing. Reading this feels like taking a walk through an ancient forest and some old, mysterious god whispering to you through stories, and, as you listen, you understand how small humans are in the grand time-scale of things, that this is the natural order of things, and, regardless of what occurs, the community of trees will survive.

Parable of the Sower

Octavia Butler

Fiction, Novel

Would recommend if you are: interested in trying apocalyptic settings for the first time, enjoyed dystopian fiction as a child, enjoys philosophical fiction.

Got the recommendation from a Vlogbrother video a long time ago. Interesting read for the year, considering that the novel is set in 2025. I think I need to reread this at a later time for it to have more significance to me.

- The setting reminds me of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, though the Earthseed religion that the protagonist develops throughout the novel gives the Parable a sense of hope amidst the suffering that I do not recall experiencing in The Road.

- The main character is very serious and sounds like the author narrating her beliefs through the voice of the character, rather than the character developing as an individual person — especially when she discusses Earthseed. But in other ways I can picture Lauren as her own character when she describes her relationships with her companions.

- I would like to reread this book at some point, more slowly and with more care.

“It’s okay not to believe in something. But don’t laugh. You know what it means to have something to believe in? Don’t laugh.”

“All that you touch / You Change. / All that you Change / Changes you. / The only lasting truth / is Change. / God / is Change.”

Practical Ethics

Peter Singer

Nonfiction, Philosophy

Would recommend if you are: interested in discussing justice regarding charity, animal rights/vegetarianism, enjoys semi-light reading on ethics.

“The question is not, Can they reason? Nor Can they talk? But, Can they suffer?“

The first time I heard the name Peter Singer was in English class in middle school, when we read his essay on the moral obligation to give to charity and discussed whether he was right. Singer’s philosophical arguments are different from other philosophy books I’ve read, in that it directly prompt you, the reader, to action, by placing and justifying a specific moral obligation to you. I am convinced by him, but I have not acted in a way that demonstrates how I agree with his principles. It remains a contradiction for my personal life.

- Singer’s argument that there is no moral justification to eat animals is very convincing to me. There are human beings — from mentally disabled people to babies — who are less intelligent, less rational than many animals, and yet they do not deserve less rights or less empathy, and it is wrong to terminate their life because of that. For the key question as to whether killing animals is justifiable lies not in how rational animals are but whether they can feel pain, and if they are capable of suffering then it is wrong to enact suffering on them. To the argument that since it is natural for food chains to exist, humans are justified in consuming prey in accordance with the food chain, Singer argues that our knowledge of the natural order doesn’t absolve us of the reason and sense of morality that humans, in contrast to other predators, now possess. Our awareness that the meat industry enacts tremendous suffering and the availability of plant-based alternatives, the reality that it is possible for many people to live a fully plant-based diet, places a moral obligation on us to switch to vegetarianism or veganism. The principle thesis is that an activity that causes more suffering is an immoral one, and I don’t have a good argument against it. And yet I still eat meat, out of preference, out of habit, out of social conventions — perhaps this will change.

- Singer’s argument on charity is also deeply convincing. If a child is drowning in front of you and by jumping in to save them you would ruin your expensive shirt, you would still be morally compelled to save the child. Morality is not diluted by geographical distance. Hence, you are morally obligated to give up your expensive shirt if by doing so a life could be saved, even thousands of miles away. Since the value of a life is greater than any personal need beyond the basics of life, there exists a moral obligation to give up all belongings and pleasures that are not necessary to live a normal life, so that the money can go towards charities that enables lives to be saved. Charity, especially significant charity — setting a significant portion of your income towards monthly donations, giving up restaurant dinners and vacations and tech gadgets — should not be a kindness but a moral obligation.

- Singer also discusses topics such as abortion, affirmative action, and climate science in this book, with similarly interesting arguments. The above two were the most memorable ones to me specifically.

- It is normal and not morally faulty to have a preference for your family and friends, and to hold internal standards for them that would be different for a stranger. Thinking and acting ethically does not require you to give up personal sentiment and relationships, but when we act, we should still consider the validity of the moral claims of those affected by our actions regardless of our personal feelings for them.

On Photography

Susan Sontag

Nonfiction, Philosophy

Would recommend if you are: a photographer, interested in philosophizing about photography, interested in media and communication.

“There is something predatory in the act of taking a picture. To photograph people is to violate them, by seeing them as they never see themselves, by having knowledge of them they can never have.”

“Photographs show people being so irrefutably there and at a specific age in their lives; group together people and things which a moment later have already disbanded, changed, continued along the course of their independent destinies.”

“A society which makes it normative to aspire never to experience privation, failure, misery, pain, dread disease, and in which death itself is regarded not as natural and inevitable but as a cruel, unmerited disaster, creates a tremendous curiosity about these events—a curiosity that is partly satisfied through picture-taking.”

Saw the cover of this book in the gift shop at the Mudam Museum of Modern Art during project week in Luxembourg. Having just started to be more comfortable with my camera then, Sontag’s observations made me think about the concept of photography in a whole new light. Absolutely fascinating arguments, presented with accurate and dynamic prose. I wonder what Sontag would say in the age of AI images being more and more undiscernable from real images.

- To photograph something is to enact power over it, to purport to know it, “putting oneself into a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge—and, therefore, like power.” The photographer attemps to “master reality by a fast visual anthologizing of it”.

- Photography appears to demonstrate the most direct version of reality, but a photograph itself cannot explain anything. What the camera photographs is reality, and people assume that by seeing pictures of something they understand it, but that is untrue — understanding begins when you want to know more than what you see. A photograph cannot explain the reason the soldiers are firing towards each other, the cause of poverty on the street, the historical causes for suffering depicted in the photograph, and because it has no explanation for what is there, the photograph is not powerful enough to make an impact without the caption to contextualize it. A photograph cannot narrate; only words can.

- Photography, despite its status as an art, resists poeticization; it is constantly debating between beautifying the subject and telling the truth. In certain ways, it is able to forgo “beauty and ugliness” in exchange for what is real: war photography, photojournalism, portraiture, street photography. Photography can aestheticize the ugly, the impoverished, the deformed people of society, through taking their portrait, their ugliness compensated for by the emphasis that they are a part of reality, and that they are interesting enough to be photographed. However, not only are they sensationalized through this process, this transformation has limits: “In photographing dwarfs, you don’t get majesty and beauty. You get dwarfs.”

- When the photograph exposes us too often to what is horrifying or grotesque makes us numb to it over time. The photograph doesn’t care if there is a compassionate response, it encourages the viewer to learn to “confront the horrible with equanimity”. To take it one step further, looking at pictures of war makes our subconscious happier because we are exempt.

- Photos are “miniatures of reality that anyone can make or acquire,” miniatures that functions of records of loss. We look at pictures of us as kids to feel how much younger we were then. “Photography is the inventor of mortality”, because the moment you take a photo of people, the people in it are gone, personalities of the past, and the people have already changed; everyone in every photograph eventually dies. In a way, photos of the past render this journey toward death more innocent, embedding the loss into a visual narrative. “Photography offers instant romanticism about the present.” A photo is proof that we were there; “In the real world, something is happening, and no one knows what is going to happen. In the image-world, it has happened, and it will forever happen in that way.”

- There is a theory of photography that assumes a common “human condition,” as all of humanity work and play and laugh and die; yet this denies the “determining weight of history” and how the existing inequalities and biases means that they don’t do these things in the same way, which may be more important than the fact that this — working, playing, dying — is what they do. An artist, a photographer, should not “universalize the human condition into joy” or “atomize it … into horror.”

- Photographing the world means being not satisfied with the world as it is and making an attempt to imagine or observe it differently. Before photography, “a discontent with reality expressed itself as a longing for another world. In modern society, a discontent with reality expresses itself forcefully and most hauntingly by the longing to reproduce this one.” Photographing the familiar makes it mysterious; photographing the mysterious makes it familiar.

- When Sontag compares the camera to a gun due to its predatory nature, I am immediately reminded of the same analogy that filmmakers in the Third Cinema film movement made: in the movement’s manifesto Towards a Third Cinema, Getino and Solanas emphasizes how the primary purpose of cinema in the modern age should not be mass entertainment or even personal artistic expression, but to liberate the masses. The camera becomes a gun “that can shoot 24 frames per second”. Though both essays adopts the analogy, Sontag presents it as predatory on a personal level, while Third Cinema sees the camera as a unique revolutionary weapon.

- You cannot photograph an event without that event being significant enough in the dominant ideology of its society to be named and categorized as an event. Photography is only useful after an event has been named; otherwise, it does not record a named thing. The politics assign meaning to the photograph beyond sheer horror and unreality.

- “The camera is a kind of passport that annihilates moral boundaries and social inhibitions, freeing the photographer from any responsibility toward the people photographed.” As if the work is done by photographing the people who suffer from poverty, injustice, exploitation. But then, what could the photographer have done otherwise?

- Some photographers believe that as an artist, what you photograph must reflect how you feel about a subject, as photography, like all art, is self-expression. But “in the vast majority of photographs which get taken — for scientific and industrial purposes, by the press, by the military and the police, by families — any trace of the personal vision of whoever is behind the camera interferes with the primary demand on the photograph: that it record, diagnose, inform.” Hints of orientalism here. This is the contradiction then, between photography as art and photography as document: the idea that “there is nothing that should not be seen” subtly supports the idea that “there is nothing that should not be recorded”. The state supports one side, the artist supports the other.

Everything is Tuberculosis

John Green

Nonfiction

Would recommend if you are: interested in narrative/memoir intertwined with science and informative writing, enjoy contemplative prose, interested in global health.

From Crash Course to Looking for Alaska, I’ve been a follower of the Green brothers (#DFTBA) for a couple of years, mostly through their YouTube channel Vlogbrothers and their podcast, Dear Hank and John. I have read most of their novels and prefer Green’s nonfiction to fiction. I have been listening to John Green discussing his interest in tuberculosis as a manifestation of healthcare inequality for a long time on their video channel, which drove me to pre-order a signed copy of Everything is Tuberculosis online.

- Throughout Green’s body of work, there is a consistent theme of resisting the use of illness as a metaphor. There is nothing to romanticize about disease, nothing romantic about purposeless, random, avoidable suffering. Romanticizing disease is similar to stigmatizing disease in that both treats the subject as other, as non-human. Tuberculosis has consistently been romanticized throughout history, which Green details in the book — but at its core it is a disease whose only goal is to be eradicated forever.

- John Green quotes Isatu, mother of Henry, the protagonist, when he asks her about her life in Sierra Leone: “Myself and my friends were woven.” Green empathizes that despite the differences in where they live and the societies they grew up in, he relates to the “joy of feeling woven into the social fabric, feeling a part of the world rather than apart from it”. But then came the war, and Isatu’s family had to leave. I think this touches on the key contradiction that many books here identifies: how much in common do we really have with one another, when we simultaneously enjoy similar things — friendship, community, comfort, work and play — yet retains them in such different, unequal circumstances? Especially when the impoverishment of one is likely caused by the historical abundance of the other? We are more common than we imagine, yet we are also more different, more unequal than we’d like to believe.

- This is the first book on global health I’ve ever read. Tuberculosis is curable and has been curable, which is the reality in most rich countries. Yet it is still the deadliest infectious disease because there is a lack of access to treatment and preventative care in many areas around the world. It is ridiculous that people die because of a lack of funding. It is not an individual problem, it is not even only a problem for the nations suffering from tuberculosis — it is a system of global health that didn’t prioritize equality.

- Statistics are futile when the number is too big to fit in one’s imagination. I cannot fathom what it means to have 1,250,000 lives end because of a curable disease. Think of your own life and the complexities within it, and try to multiply that by 1,250,000. You cannot. The injustice is unimaginably large, Makes me remember the quote about how strange it is that you can simply physically kill someone and they no longer exist. Like breaking the glass of a window on the empire state building and have the building crumble.

“Death is natural. Children dying is natural. None of us actually wants to live in a natural world.”

Breakfast of Champions

Kurt Vonnegut

Fiction

Would recommend if you are: interested in comic/satirical novels, absurdist humor.

First time I picked up Vonnegut was Mother Night in the school library. Slaughterhouse Five has been on my reading list for quite a while, and I’m looking forward to picking it up next year.

- It’s a story about Kilgore trout, but the author’s meta-commentary is explicit. Most of what you read is a bit nonsensical and funny and exaggerated until the author says something wise and/or depressing through a witty pretense.

- There are lots of hand-drawn doodles.

- I wish I remembered more from the book. There were a few lines I really enjoyed, such as Vonnegut’s comment on the English curriculum in schools: “They were told that they were unworthy to speak or write their language if they couldn’t love or understand incomprehensible novels and poems and plays about people long ago and far away, such as Ivanhoe.” However — maybe since I read it in January — the plot did not leave a lasting impression. I would like to reread this book.

“I have no culture, no humane harmony in my brains. I can’t live without a culture anymore.”

“There is madness and crazyness, but bad ideas give craziness shape and direction … The bad idea in question: that everyone else was a robot and only I know what pain is and have choices to make.”

“Creative works makes poor people feel stupid and pretends that life is a story with leading characters, minor characters, significant details and insignificant details, it had lessons and tests and start and middle and end. The author wants to write in a way that makes any person exactly as important as the other. And people will realize that there is no order.”

Ways of Seeing

John Berger

Nonfiction, Essays

Would recommend if you are: interested in theorizing the visual arts and art history, enjoyed Susan Sontag.

“When we ‘see’ a landscape, we situate ourselves in it. If we ‘saw’ the art of the past, we would situate ourselves in history. When we are prevented from seeing it, we are being deprived of the history which belongs to us. Who benefits from this deprivation? In the end, the art of the past is being mystified because a privileged minority is striving to invent a history which can retrospectively justify the role of the ruling classes, and such a justification can no longer make sense in modern terms. And so, inevitably, it mystifies.”

“Every one of her actions – whatever its direct purpose or motivation – is also read as an indication of how she would like to be treated. If a woman throws a glass on the floor, this is an example of how she treats her own emotion of anger and so of how she would wish it to be treated by others. If a man does the same, his action is only read as an expression of his anger. If a woman makes a good joke this is an example of how she treats the joker in herself and accordingly of how she as a joker-woman would like to be treated by others. Only a man can make a good joke for its own sake.”

Graduation gift from Ajay. Unfortunately lost with the rest of the baggage from the Sarajevo-Istanbul flight, but fortunately I finished the book during the travels before then.

- When something visual is presented as “art” (e.g. placed in a gallery or museum), people apply their preexisting, sometimes subconscious assumptions about art to the piece of work.

- There is no value-neutral objective view of the world. There isn’t even a version of that reality. The world as it is includes the consciousness of yourself that sees it.

- All of history is the relationship between the present and the past. Fear of the present leads to mystification of the past.

- Berger theorizes that when we “see” a painting, we partially place ourselves within the setting of the painting, which means we place ourselves within the history that the art of the past represents. The existing barriers and mystification of art (e.g. lack of public art education, museum entrance fees, skyrocketing prices for art auctions) prevents us from seeing and engaging with the history that belongs to us. This is intentional: by doing so, the minority with political and financial power can retrospectively justify their dominion over the public; since the justification is illogical in today’s democratic society, the art has to be mystified to be a convincing proof of superiority. (This is my understanding of the quote on the left, which is one of my favourite quotes from this year of reading.) The above is a fascinating argument for advocating art history education in public school curricula and eliminating entry costs to art museums, or perhaps an explanation for its lack thereof. Also example of how knowledge and the means/barriers to acquiring it are almost always political.

- In the age of mechanical reproduction, art is no longer limited to its physical space and can be reproduced in different forms by individuals anywhere, so long as there is the technology for it. Therefore, ordinary people are able to curate their own space with the art they choose — “letters, snapshots, reproductions of painting, newspaper cuttings, original drawings, postcards” — which demystifies the art. The individual curator who decorates their room with art they print makes art no longer confined to museums and galleries; through your curation you relate the art to “every aspect of experience”. It is no longer a tool used by the privileged class. The meaning of art should belong to those who can apply it to their own lives, not to “a cultural hierarchy of relic specialists”.

- The visual arts have evolved from being tied to a particular place in time (e.g. cave paintings, murals), which sets it apart from daily life as a ritual, to being commissioned by the aristocracy and became privatized in homes and palaces, which gave the owners of the art the authority that belonged to the artwork itself. But now, with the ability to reproduce art through printing, art became possible to surround us the same way “as a language surrounds us”. That authority of having the means to preserve art is no longer scarce.

- Most people still assume — are led to believe — that to appreciate art today is still only possible in the way that aristocrats approached art, however that is. It is still seen as high-end and classy and ultimately exclusive, but in reality more and more people have the ability to use and produce art to define their world and personal/historical experience, especially when “words are inadequate”. Art becomes accessible as a tool to enrich “the experience of seeking to give meaning to our lives, of trying to understand the history of which we can become the active agents.” There is no longer an authority of art but a language of images, and anyone can use language.

- In the oil paintings of the past, men and women are portrayed differently: men in images always attempt to show his power over people and things, while women attempts to enhance her presence, often to men, both in the image and to the assumed male viewer. Women are conscious of how they appear, because it is important to her success and how she is treated by men. All of her actions are an indication of how she would like to be treated, instead of just an expression of her personality. Reminds me of what Margaret Atwood said about how women are their own voyeur.

- Difference between being naked and nude: to be naked is just to be oneself, but to be nude is to “be seen naked by others and yet not recognized for oneself”. The nude has to be objectified, it is passive, on display, but “nakedness reveals itself”. It is to be “without disguise” or to make your own skin, your body your disguise. “Nudity is a form of dress”. In nudist European paintings the protagonist is the voyeur, the male voyeur. The figures assume nudity for him.

- Glamour came from normalized social personal envy. This envy is possible in a society that realized democracy is a good but has not reached it, where “the pursuit of individual happiness has been acknowledged as a universal right, yet the existing social conditions make the individual feel powerless” and they either realize the contridiction and join the anti-capitalist movement, or lives with the envy and daydream forever. “The working self envies the consuming self” of the future.

- Publicity “turns consumption into a substitute for democracy. The choice of what one eats (or wears or drives) takes the place of significant political choice”, masking what is actually undemocratic about the society one lives in.

The Politics of Design

Ruben Pater

Nonfiction, Essays

Bought the book at a airport in Berlin, I think? First fun informational book about design I’ve read. Gave to Robbins after finishing it.

- Photography was mechanically engineered with white models and light skin. If a black person and a white person in one image, one would be too bright or too dark.

- The Taylor Swift sweatshirts made it in the book as an example of a design that forgot to consider the social context it was in.

- The Family of Man photo exhibition was supported by the CIA as propaganda against the Soviets, but it wasn’t recognized as propaganda — “The millions that visited the The Family of Man exhibition were under the impression this was a normal photography exhibition about the universal values of humanity.”

- I don’t remember most of the examples now, but from what I recall, it’s a fun and humorous read about visual design.

Would recommend if you are: interested in media and communications, interested in visual design and its political aspects, want a light and interesting introduction to topics like advertisement design .

Orientalism

Edward Said

Nonfiction, Post-Colonial Politics

Would recommend if you are: interested in post-colonial studies, a social science student studying in Europe or America, interested in political/historical theory, or plan on studying politics seriously.

“Narrative asserts the power of men to be born, develop, and die, the tendency of institutions and actualities to change, the likelihood that modernity and contemporaneity will finally overtake “classical” civilizations; above all, it asserts that the domination of reality by vision is no more than a will to power, a will to truth and interpretation, and not an objective condition of history.”

“For a myth does not analyze or solve problems. It represents them as already analyzed and solved; that is, it presents them as already assembled images, in the way a scarecrow is assembled from bric-abrac and then made to stand for a man.”

Spent a couple of months on this one. For nonfiction, this is my book of the year — I’ve learned so much about the relationship between colonialism and the Western system of knowledge in the status quo. There is much, much more I want to note down for this book. Would probably come across this text again in university.

- The author’s position as an Arab academic living and teaching in the Western world is explicitly stated to influence his arguments in the book. Laying out the position from which one is writing and acknowledging that it is not a neutral, value-free argument feels like a more honest and convincing introduction than to claim that one is not biased.

- The whole idea of the Orient, the non-Western world — most notably in Asia, Africa, and the Arab world, specifically in this book — is created by the West via a “system of representations … that brought the Orient into Western learning, Western consciousness, and later, Western empire.” The Orient has to be represented and spoken for by the Western academics that gradually builds an archive of knowledge about the Orient, about how the people and culture behaves, about the language and the architecture and the politics, and by establishing this system through categorization and record, the idea of the Orient becomes fixed. Orientalism assumes that the entirety of the non-Western world can be viewed “panoptically”, that there is nothing unarticulatable or hidden from the sight of scholars. Combined together, the Orient is thus imagined to be unchanging, unable to evolve like how Western culture evolves, which means it can be recorded and understood in its entirety. This is why any attempt to characterize the Orient as something other than how it has always been characterized is viewed by Western academia as threatening: “What seemed stable — and the orient is synonymous with stability and unchanging eternality — now appears unstable. Instability suggests that history, with its disruptive detail, its currents of change, its tendency towards growth, decline, or dramatic movement, is possible in the Orient and for the Orient.”

- Western academics, the heads of the Middle East and Far East studies at university and research institutes, has always characterized the Oriental man and woman as a fixed and specific caricature, which thus represents the entire population: backwards, conservative, undeveloped, impoverished, liars, stingy, arrogant, ignorant, weak … judgements littered throughout academic literature of a supposedly “objective” study of the Arab world. This extends to judgements about arab politics and religion — intolerant, unable to compromise, perpetual conflict. Even academics that lives within Arab countries and speak fluent arabic make characterizations of what an Arab is that ultimately fails to encompass the diversity of Arab culture, the individuality of each Arab person, and the everchanging state of Arab culture, much less the academics that never stepped foot on Arab land. This is orientalism in essence, a way of perceiving the Arab world via an endless system of static representations.

- Orientalism as an academic field (often taking names such as “Asian Studies”), is a “school of interpretation”; the “objective discoveries” its scholars make regarding translation, dictionaries, historical records and so on cannot escape from the fact that the truths they produced, “like any truths delivered by language, are embodied in language”. Language itself is “a sum of human relations, which have been enhanced, transposed, and embellished poetically and rhetorically, and which after long use seem firm, canonical, and obligatory to a people.” — recording the Orient in the English language already starts to legitimize the Oriental understanding of the world.

- Characterizing the oriental world as overall “lesser”, weaker, more uncivilized not only reassures the superiority of the European race and culture, but provides the justification for the violent domination and exploitation of the Oriental peoples. Knowledge is power: the Orient as a system of knowledge ultimately serves Western imperialism.

- It is impossible to explicate oneself and one’s research from the entire Oriental system of knowledge, because of how entrenched it is in the Western academic world for someone reading and writing in English. But being aware of it is allows you to be conscious of how Orientalism manifests in your arguments, which makes change possible.

- Orientalism is a myth told about the Orient that claims to explain the entire homogeneous story of Oriental civilization. This is why individual narrative matters, why oral history matters, why fiction matters: narratives of individual stories, in contrast to an encyclopedic presentation of a civilization, emphasizes that the fixed “vision” the public has regarding what the Orient is, is in its entirety constructed by a hierarchy of power, a desire for truth and knowledge and interpretation, not an unchangable objective condition of history. What is taught in Asian Studies is not indisputable truth, as much as authority the professor wields. It is possible and not even particularly difficult to articulate a different interpretation, through individual narratives and storytelling in fiction.

This Earth of Mankind

Pramoedya Ananta Toer

Fiction, Novel

Would recommend if you are: interested in Indonesia at all, enjoys reading fiction, interested in the impacts of colonialism (especially explored through literature), likes to read about unsually smart teenagers.

For some reason I have no photo records of reading this book, but this was a far better introduction to Indonesia for me than the previous book: there are less historical facts, but I understood more about the role social class and ethnic origin played in colonized Indonesia through Minke’s story with Annelies. Great characterization, and it was clear that the social context the author lived in drove the novel to existence, as the conditions of all the characters are deeply tied to their social ties within their society.

What the book discusses in regards to education inequality within colonized Indonesia, the transformative power of education and media that enables Minke to print anti-colonial articles under a pseudonym, the relationships between (male) Dutch settlers and (female) indigenous “natives”, the unequal social status … all the themes mentioned in the book have appeared repeatedly as I learned more about Indonesian history and culture after I arrived. I would love to reread the story again and to finish the quartet. Will add more notes here when the reread occurs.

Hawker Colours: Melamine Tableware in Singapore

In Plain Words

Zine

Would recommend if you are: interested in graphic design and its evolution in a cultural context, interested in Singapore / lives in Singapore, since I havn’t found a copy online yet.

Bought in a small bookstore/craft shop in Singapore over the summer! Went to a lot of hawker centers during my time there and found the culture fascinating.

- Probably the most aesthetic book I’ve read this year.

- I absolutely adore books like this, taking something so small and seemingly insignificant and diving into it, showing the reader how it’s not only beautiful and interesting but full of stories: how the factories decide which colors to manufacture, the feuds between different stalls, the struggles of the central kitchen to clean and redistribute the dishes … and from the small thing you can raise questions about the conflict between tradition and modernity, about what is the price we’re willing to pay for convinience. Maybe this is the magic of anthropology. How cool it is, I think, that someone paid enough attention to something to tell the world about why it’s so interesting.

- Eating is not just survival; it’s ingrained in culture everywhere. Hawker culture is in the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage list!

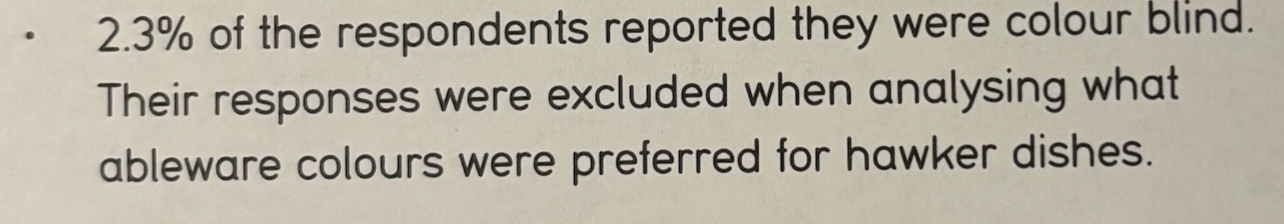

- This is my favourite unintentionally funny quote from this year: while describing the methodology and results of a survey, which aims to examine the relationship between different hawker plate colors and the food served, this was written:

Maybe You Should Talk To Someone

Lori Gottlieb

Nonfiction, Memoir

Would recommend if you are: interested in anecdotal stories about therapy and how therapists work.

Saw it multiple times on a recommended list while looking for something new and out of my range to read. Nice light read, good for a break between more serious books.

- Each patient’s story was very touching. I really enjoyed how the book humanizes not only the patients, especially the initially unlikable ones, but also the therapist (the author) herself. People act badly because of events that, if you had been through them, you can’t guarantee you won’t act the same way.

- In different ways, all the patients struggle with dealing with change. “We are afraid of change and we are afraid of not changing.”

- Interesting framing for the key psychological/developmental arc of each era in our lives:

- Baby (hope)—trust versus mistrust

Toddler (will)—autonomy versus shame

Preschooler (purpose)—initiative versus guilt

School-age child (competence)—industry versus inferiority

Adolescent (fidelity)—identity versus role confusion

Young adult (love)—intimacy versus isolation

Middle-aged adult (care)—generativity versus stagnation

Older adult (wisdom)—integrity versus despair

- Baby (hope)—trust versus mistrust

“In therapy we aim for self-compassion (Am I human?) versus self-esteem (a judgment: Am I good or bad? )”

Notes of a Native Son

James Baldwin

Nonfiction, Essays

Would recommend if you are: interested in race relationships in America, interested in studying slavery and its complex psychological impacts on Black Americans today, interested in comparisons of race relations to Africa and Europe, or if you enjoy achingly poetic and observational essayist prose.

“One writes out of one thing only—one’s own experience. Everything depends on how relentlessly one forces from this experience the last drop, sweet or bitter, it can possibly give. This is the only real concern of the artist, to recreate out of the disorder of life that order which is art.”

“Society is held together by our need; we bind it together with legend, myth, coercion, fearing that without it we will be hurled into that void, within which, like the earth before the Word was spoken, the foundations of society are hidden.”

“He had lived and died in an intolerable bitterness of spirit and it frightened me, as we drove him to the graveyard through those unquiet, ruined streets, to see how powerful and overflowing this bitterness could be and to realize that this bitterness now was mine.”

“The African before him has endured privation, injustice, medieval cruelty; but the African has not yet endured the utter alienation of himself from his people and his past.”

“… the betrayal of a belief is not the same thing as ceasing to believe.”

After finding Nobody Knows My Name in the school library a year before, I fell in love with Baldwin’s essays on race, sexuality, and social inequality. This is the second book I’ve read from him. Baldwin is one of my favourite authors in terms of prose, argument, and the humanity in his writing. I have a special fondness for essays written by fiction writers: Giovanni’s Room is brilliant, but Baldwin’s essays speaks to me like how a friend, a mentor would speak to me.

- America does not like to be reminded that it has a racist past, which clearly seeps into the present. (In fact, Sontag suggests that people in power especially do not like to remind the public about the past as it was). But the people of both races, white and black, needs to look to history to prevent history from occuring again. And it is partly because of this refusal to truly come to terms with the past that the Black american remains alienated from their history, that this alientation is the American experience for anyone that is not white.

- Baldwin described his reading of European literature as beautiful yet ultimately alien, since it was “not [his] heritage”: “These were not really my creations, they did not contain my history; I might search in them in vain forever for any reflection of myself.” How far can the human condition encompass? If I have understood literature as something that can rouse empathy and foster understanding across boundaries of time and space, race and sex and nationality, then was I wrong if I had not realized this alienation? Maybe being immersed in literature — and a foreign language — makes it easier and easier for one to pretend.

- You can only write meaningfully, authentically, out of your own experience. You write about life as you have lived it, and only by drawing material out of your lived experience can the work, the message, be real. In the same line of thought, what Martin Scorcese said rings in my head constantly: “The most personal is the most creative.”

- Baldwin argues that someone who is too outwardly, excessively emotional, the “sentimentalist”, is in reality unable to feel, and the “wet eyes” are in fact “the mask of cruelty”. Baldwin talks about this in regards to the sympathy demonstrated by some white residents in his neighbourhood. I’m not sure I exactly agree, but I see what he means when I interpret his words as condemning those who believes that showing sympathy is enough of an act in the face of injustice, while mere sympathy changes nothing.

- Baldwin is very cautious of assertions or causes that aims to represent a large group of people: when he talked about truth as “devotion to the human being”, he emphasizes that he refers to the individual’s “freedom and fulfillment”, which cannot/should not be surveilled and controlled by the state. Baldwin contrasts his understanding to a “devotion to humanity”, a broader concept that is more likely than not to be reduced to a cause — communism, nationalism, ideologies that says to benefit large, assumed homogenous masses — that almost always results in violence.

- By ignoring or avoiding the complexity or ambiguity of others, whether it is as individuals or as identity groups of people, we also become unable to see ourselves as multitudinous individuals. How we treat ourselves reflects on how we treat others, and vice versa.

- How much grace do we give to good intentions when the execution of these intentions still perpetuates what the novel aims to protest? Baldwin’s essay discussing the anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the liberal response to criticisms of the novel: the stereotypes it makes of Black people “are forgiven, on the strength of these good intentions, whatever violence they do to language, whatever excessive demands they make of credibility.” Yet, undeniably, it was a vital book for abolitionism in the US. What is the right attitude toward a work that is still harmful yet aims to make progress in an even more harmful world? What right do the supporters, who feels virtuous for having read the book, have to ask the book’s subjects to set aside what the author wrongfully assumes?

- The oppressor and the oppressed, despite their conflict, live in the same society and hence shares the same values underwhich one oppresses and one is exploited. Their existence depends on the same reality. And so even when the existing reality is oppressive, the oppressed still attaches their humanity to what is there, they accept that in this reality it is possible to be subhuman — there is no space to imagine a new society. You are judging yourself by the standards of the powerful, which they use to judge you. You internalize those standards; this applies to many relationships in society.

- Humans are social beings, but they are also not only social beings.

- Baldwin’s view on culture and tradition is very realist. What tradition is, in essence, is the strategy of suvival and surviving with dignity that a people has formulated through centuries of painful experience. Tradition becomes tradition because doing so allowed them to live a human life. “No people come into possession of a culture without having paid a heavy price for it.” What we call culture now is inevitable to have formed. It is not in itself desirable or undesirable, “being nothing more or less than the recorded and visible effects on a body of people” of the trauma they have suffered as a people.

- How Baldwin describes white America’s perception of black american life here — incapable of complexity, development, change / uncivilized, uncultured, angry, in servitude, etc. — pararells what Said discussed regarding orientalism, how the oriental system of representation fixes a people and presents them as incapable of complexity and change.

- Racism is entrenched into all media, even anti-racist media: in the movies after Birth of a Nation, filmmakers that make anti-racist films that argue against the then-commonly held perception of how black people are amoral — they could only do so by arguing against the idea that “Negroes are not white”. [to expand]

- When Baldwin comments on the relationship between Black people and Jewish people in American society, he is careful to state that his comment on the overall relations between these groups being antagonistic “is not meant to imply that individual friendships are impossible or that they are valueless when they occur.” It is a good reminder of agency: individuals almost always do have a choice and is capable of going against what academics are saying about “groups of people”, and assumptions made — well-argued assumptions, but still generalizations — about the dynamic cannot be applied to individual relationships that, in reality, do not perform these dynamics.

- When people no longer have hate to hide behind, they must deal with the pain. Hatred destroys the person who holds it. It’s the same principle over and over again: “hurt people hurt people.”

- There are two views on reality that are in constant battle with each other: one accept things for what it is, acknowledges that injustice has always been a part of any society — yet the other argues that you must never accept injustice simply because it is reality now, and you must always fight it when you see it. To accept or to change; both are equally strong voices that follow you throughout your decisions in life.

- The danger of institutions is that by instinct they sound protective, just, unbiased, orderly, and equally good for everyone, yet the reality is that institutions are often “outmoded, exasperating, completely impersonal, and very often cruel” towards those who were not the intended benefactor of these institutions.

- Knowledge and recording as information as means of control has been a continuous theme in many books I’ve read in the past year. To describe is to know, to know is to have the ability to control and dominate. “Every legend, moreover, contains its residuum of truth, and the root function of language is to control the universe by describing it.”

The Bell Jar

Sylvia Plath

Fiction, Novel

Would recommend if you are: interested in unstable narrators, interested in feminist fiction, liked Sally Rooney’s “Normal People”.

First (and last) Bridge Year book club book … Been on my reading list for a very long time and finally got to it. Unfortunately, the book club discussion never occurred. I would have liked to discuss this book in detail, but alas. Would reread.

- The book muses a lot about womanhood and how women are expected to behave in a patriarchal society. There are certain books where I can sense that the author is speaking directly through / as the main character, and this book is one of them, which makes sense since it’s semi-autobiographical. I can understand why it’s a modern classic, in terms of how clearly she articulates the experience of being a young, talented, yet isolated woman in a male-dominated world.

- The prose is very poetic, and there is a continuous sense of the character being disconnected / alienated from the world and from other people in her life, a disconnection that becomes extreme toward the end of the novel.

“I said to myself: ‘Doreen is dissolving, Lenny Shepherd is dissolving, Frankie is dissolving, New York is dissolving, they are all dissolving away and none of them matter any more. I don’t know them, I have never known them and I am very pure. All that liquor and those sticky kisses I saw and the dirt that settled on my skin on the way back is turning into something pure.’”

Regarding the Pain of Others

Susan Sontag

Nonfiction, Essays

Would recommend if you are: interested in examining how media portrays suffering, the relationship between photography and war, enjoyed “On Photography”.

“Memory is, achingly, the only relation we can have with the dead.”

“It also invites them to feel that the sufferings and misfortunes are too vast, too irrevocable, too epic to be much changed by any local political intervention. With a subject conceived on this scale, compassion can only flounder—and make abstract. But all politics, like all of history, is concrete.”

“People want to weep. Pathos, in the form of a narrative, does not wear out.”

“To speak of reality becoming a spectacle is a breathtaking provincialism. It universalizes the viewing habits of a small, educated population living in the rich part of the world, where news has been converted into entertainment—that mature style of viewing which is a prime acquisition of “the modern,” and a prerequisite for dismantling traditional forms of party-based politics that offer real disagreement and debate. It assumes that everyone is a spectator. It suggests, perversely, unseriously, that there is no real suffering in the world.”

Another banger of a book by Susan Sontag! This was written after On Photography and partially critiques it.

- The fact that war is destructive to human life is not in itself an argument against all wars, unless one is against any use of force. Sontag references Simone Weil’s The Iliad, Or, The Poem of Force in how war makes people become things.

- People often assume that there is a universal human reaction of horror when people are shown war photographs. But the reaction is not universal: it can arouse a rally for peace, a cry for revenge, or an apathetic “it-is-what-it-is” attitude towards the ongoing violence of the world.

- Sontag argues again here like how she argued in On Photography: a photograph can show the viewer how destructive war is — or, rather, how a certain of war that physically targets civilians, is — but it cannot narrate. Looking at a photograph makes the viewer assume that they understand, without a caption it only presents the viewer the horrifying trauma of nameless, generic victims, and it doesn’t reveal anything about the politics or history that resulted in the violence shown. The namelessness makes the victims of violence abstract, which makes compassion less actionable. Captions will be added to serve the mainstream ideology. The captions are often melodramatic, despite all the emphasis on the image representing reality realistically. Even so it is fine to remember through photographs, but it is not fine to remember only through photographs.

- A photograph is readable to anyone; a nuanced, written account will always have a limited number of readers. The photograph, becoming more and more versatile in different circumstances and being by definition objective — though there is always a point-of-view due to the person that takes them, and to photograph is to frame is to exclude and compose, and even a destroyed landscape is still a landscape — overtakes the spoken word and the printed word as the recorder of reality, and photographs have the greatest authority and inmediacy in confirming an event has occured. But now we are capable of generating hyperrealistic images that the human eye can’t determine if it’s real or not all the time. Then what of the truth-value of photography?

- To the militant, identity is priority: a child dead on the streets of jerusalem is seen by the Israelis first as a Jewish child killed by a Palestinian suicide bomber, before seeing them as a dead child; a child dead on the streets of Gaza will be seen by the Palestinians as first a Palestinian child killed by the occupying Israeli regime before seeing a dead child.

- The awareness that war is occuring elsewhere is mostly built by photographs. To photograph an event makes it real; the photograph is the freeze-frame of memory. Because of this, the more shocking photographs are, the more attention they gather — there is an incentive for the photographer to hunt for more dramatic pictures; shock became a source of value, and it is a powerful motivator for action. The more horrifying the image, the more celebrated the photographer, the more the image of agony and ruin becomes the official image of war in our minds. Therefore, some people begin to develop a sort of satisfication when they no longer flinch at the images, while others pride themselves on the fact that they still flinch. Shock is even sometimes accompanied by awe at the suffering: in Christrian theology, suffering is spectacular. And there will never be a balance in the news between shock and normality, because shock sells. No one will ration horror. There are some parts in the human psyche that even enjoys looking at suffering. So the view on suffering diverges: suffering as spectacle, as sacrifice, as something that one could potentially find beauty in — and the modern view, the view that suffering is a problem that has to be fixed, that there is no inherent meaning to pain.

- Eventually photographs are seen to represent reality so much that the photograph — the spectacle, the shock — becomes the representation for reality in the place of reality itself. There are only representations through media.

- Photographs aestheticizes: it makes the subject more beautiful, more horrifying, more feeling in one way or another, when it is not that way in real life. It objectifies: it makes a subject and its environment something that another can posess in some way. There is always a faint feeling of guilt along with photography, of indignation: photographers have no right to flatten someone’s suffering, to experience and share their pain at a distance. No right to commericalize the suffering of others, no right to make them a spectacle. How do I be a photographer in a way that emphasizes the humanity of the people in my frame?

- A photographer in war, especially when they are personally affiliated with one side, it becomes very difficult to take photographs value-free for them immediately. To practice self-censorship is to be patriotic and safe.

- The more exotic and remote the subject of suffering, the more likely we can see their dying faces. The oriental are afforded less humanity than the occidental, as they always have been. Moreover, perpetually showing images of violence and trauma from a place far away from the West reiterates two things to the audience: that there is injustice and you should be outraged, and that this is the sort of thing that happens in that sort of place. These photographs “nourish belief in the inevitable tragedy” in “those parts of the world”.

- Victims describes war from “it feels like a dream” to “it feels like a movie” due to Hollywood’s big budget war films.

- So what is collective memory? “All memory is individual, unreproducible—it dies with each person. What is called collective memory is not a remembering but a stipulating: that this is important, and this is the story about how it happened, with the pictures that lock the story in our minds.” Not that there aren’t events everyone remembers, but that memory becomes collective when someone in power engineers it to be, and to be personal historians, to develop a memory outside of that mandate, is to regain agency in a correct memory laid out for us. And that is why it is important to learn and read. Because some memories are not created by museums because they are “too dangerous to social stability to activate and to create”, such as the absence of a museum of slavery in Washington DC, where there is a museum of the Armenian genocide but not of slavery. “To have a museum chronicling the great crime that was African slavery in the United States of America would be to acknowledge that the evil was here.” Most of american history has framed America to be pure and evil elsewhere, and not on its own soil. So does the histories of other countries.

- Compassion that is not followed by action soon fades; the compassionate agent feels powerless because if they feel that there is nothing “we” can do — who is we? — or “they” can do — who is they? — people feel powerless and therefore apathetic, cynical, bored.

- “Remembering is an ethical act” versus “but history gives contradictory signals about the value of remembering in the much longer span of a collective history … too much remembering (of ancient grievances …) embitters. To make peace is to forget. To reconcile, it is necessary that memory be faulty and limited.” But the state benefits sometimes when people stay embittered, I think.

- Just because news now can be instantly shared worldwide doesn’t mean our capacity for sympathy or to act on that sympathy became larger. As long as I the viewer who watches scenes of war unfold on television and feels sympathy for the poor dying children, I am innocent. For some reason my sympathy absolves me of my complicity in a system that gives me convinience at the cost of making the war go on. And everyone who has been in a war will tell you that your sympathy is not accurate. You will never know what it was really like, how horrible it really was, because no matter how many images you see, you weren’t there.

Normal People

Sally Rooney

Fiction, Novel

Would recommend if you are: a young adult, thinking about love and relationships, looking for something quiet and touching to read.

Book that has been on my booklist for a while.

- One of the ways I decide if a story is well-written is if I am able to see the flaws of each character, flaws with real consequences on their lives, yet I am still very fond of the characters and wishes for them to be happy, to come to terms with themselves and accept them for the whole of who they are. This novel has accomplished this for me. I think it is worth the praise it receives.

“It suggests to Connell that the same imagination he uses as a reader is necessary to understand real people also, and to be intimate with them.”

“It’s true, he feels his future is hopeless and will only get worse. The more he thinks about it, the more it resonates. He doesn’t even have to think about it, because he feels it its syntax seems to have originated inside him.”

“It was culture as class performance, literature fetishised for its ability to take educated people on false emotional journeys, so that they might afterwards feel superior to the uneducated people whose emotional journeys they liked to read about … Literature, in the way it appeared at these public readings, had no potential as a form of resistance to anything.”

“She closes her eyes. He probably won’t come back, she thinks. Or he will, differently. What they have now they can never have back again. But for her the pain of loneliness will be nothing to the pain that she used to feel, of being unworthy. He brought her goodness like a gift and now it belongs to her. Meanwhile his life opens out before him in all directions at once. They’ve done a lot of good for each other. Really, she thinks, really.

People can really change one another.”

The Safekeep

Yael van der Wouden

Fiction, Novel

Would recommend if you are: a fan of historical fiction, (somewhat) interested in Dutch WWII history, queer, looking for a novel to read.

Before graduation, my high school English teacher, who is a Dutch woman, said she wanted to include this book in next year’s English reading list. It found my way into my reading list then, and, when I missed my English task, I dug through my booklist and picked it up.

- Most beautiful love story I’ve read this year. I will be careful not to spoil this, because I am very glad about the fact that I did not see it coming at all. It is so achingly beautiful and fulfills what I talked about above in regards to Normal People. I’d say this is my first historical fiction book and showed me the magic of that genre.

- I don’t think I’ve read a book where the author has curated a sexual/sensual experience so effectively and with so much emotion before.

- I have realized that I am very fond of books / stories that personifies the environment — a house, a city. I am drawn to stories where the city has its own pulse, speaks to the characters in its own way; where the house itself is alive (which ranges from this book to Ray Bradbury’s There Will Come Soft Rains). I like reading about a character’s attachment to a physical place, and how that place is transformed — from the inanimate to the personified — by the character’s attention to it.

“Home, when she arrived, welcomed her with relief. There you are, said the dim light in the kitchen, left on for comfort. I’ve waited up for you, said the rattle of key in the door.”

“What was joy, anyway. What was the worth of happiness that left behind a crater thrice the size of its impact.”

“She had held a pear in her hand and she had eaten it skin and all. She had eaten the stem and she had eaten its seeds and she had eaten its core, and the hunger still sat in her like an open maw. She thought: I can hold you and find that I still miss your body. She thought: I can listen to you speak and still miss the sound of your voice.”

Brave New World

Aldous Huxley

Fiction, Novel

Would recommend if you are: interested in dystopian fiction, interested in political philosophy, looking for a classic that’s extremely engaging to read.

Read once during my childhood dystopian fiction phase, but for some reason wanted to read it again after many years. Still as genius in worldbuilding as I had remembered it, and still as terrifying.

- I think this book partly proves to me that rational argument and philosophizing must go hand in hand with fiction. I have read and thought about how happiness couldn’t be the highest good over and over again in different texts, but only this book has made me feel the horror of a reality that maximizes happiness to the extreme; feeling is a uniquely powerful argument. Freedom to choose, freedom from having one’s character intentionally engineered throughout childhood, freedom to be a person, not because to be a person means to suffer but to have the capacity to suffer because of real choices, is more important than happiness. But who can really say no to a world where there is no disease, no heartbreak, no pain? No one really enjoys suffering; but the need for something real makes one accept the suffering that comes along with it. But then where does this desire for authenticity come from?

- Someone who has been conditioned to like the social reality designed for them would never be unhappy. If I were born that way, I wouldn’t have complained about a lack of “freedom” either. But this wouldn’t be a better society, I think, as someone who does not live in that society — though who can say no one has been conditioned to believe certain things about their reality?

- What makes the book more terrifying is not only the society it describes, but the fact that speculative fiction draws its premises from the consumerist society we’re already in and stretches it to the extreme. The conditions for making the society of Brave New World is already here, and we are partly the way the people in the novel are. When we are horrified at the people in the stories, we are horrified by parts of ourselves.